Is the Surgery Center of Oklahoma Cheaper than Hospitals?

Probably. But you have to know how to look.

The Hospital Price Transparency rule went into effect in January 2021 with the aim of making hospital care, which currently accounts for a record 6.1% of U.S. GDP and 31% of healthcare spending, more affordable by promoting price competition. The rule shines a light on the black box that is hospital prices by requiring all hospitals operating in the U.S. to make publicly available an up-to-date, machine-readable list of payer-specific prices for standard charges.

While healthcare prices are typically opaque, there have been some notable exceptions. In 1997, tired of hospital bureaucracies, third-party payers and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)’s new physician payment system, Keith Smith and his friend Steve Lantier, both anesthesiologists working at large hospitals, walked away from their practices and opened the Surgery Center of Oklahoma (SCO). SCO was founded on the idea that bureaucratic insurance and hospital systems drive up healthcare prices. SCO's model is different: Patients spend their own money up-front and receive a binding quote: That pricing model, just like a haircut or an oil change, is how most of the economy operates but was revolutionary in our highly regulated healthcare sector, driven by third-party payers.

The surgery center’s story is fascinating. For more details we’d point interested readers to this Discourse Magazine interview by Bob Graboyes. While there are many reasons why this up-front model may enable SCO to offer lower prices, we set out to answer a simpler question: Is SCO actually offering lower prices? What follows is an attempt to answer this through what is very much an exploratory analysis using newly available Hospital Price Transparency data.

Trying to make it apples-to-apples, we wanted to compare some SCO prices to cash prices for the same service (as opposed to insurer-negotiated rates), both inside and beyond the state of Oklahoma. We further narrowed our search to procedures performed on an outpatient basis and removed children’s, psychiatric and long-term care hospitals from our dataset.

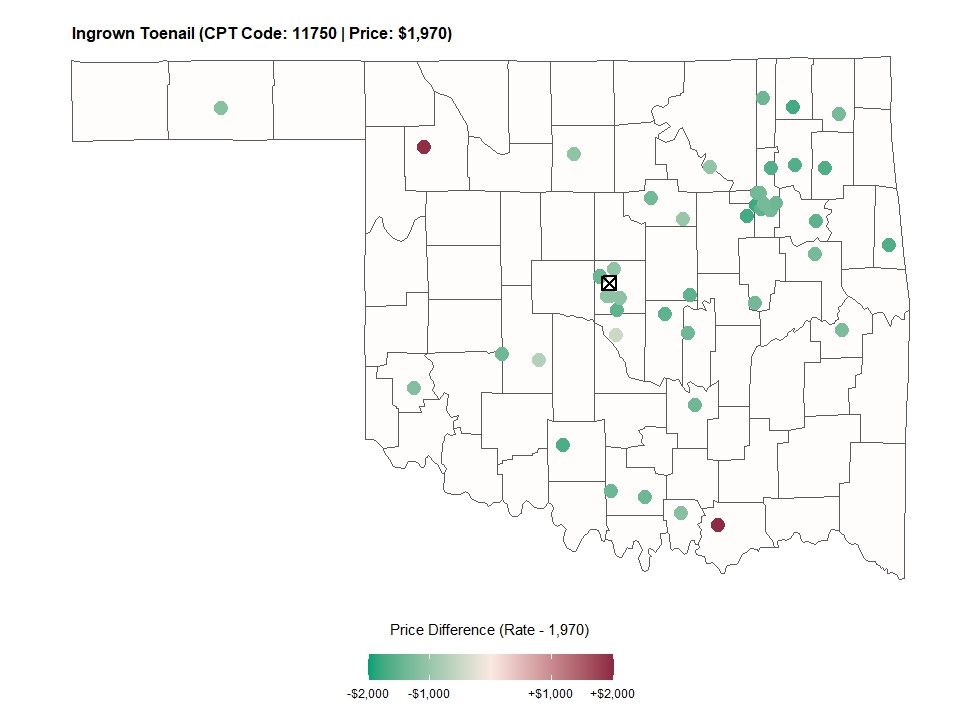

We decided to start with prices for ingrown toenail surgery, a common condition caused by improper nail trimming. We plot each Oklahoma hospital price against a baseline of $1,970 dollars, the price offered by SCO, so that the color indicates the relative price difference.

The results were surprising. To the extent there was a bidding war, it seemed the surgery center was losing, with most hospital rates far lower than SCO’s. In fact, 85% of providers charge cash rates under $1,000. We checked a few additional procedures but found similar results, both in Oklahoma and nationwide, so in the end we reached out to Dr. Keith Smith, medical director at SCO, who told us:

“One complicating factor is that we do not charge for incidental procedures, all of which are coded and charged by hospitals. For instance, if we are repairing someone's rotator cuff, we don't charge for the distal clavicle excision or the acromioplasty that typically accompany this procedure.”

Going with that example, the median hospital cash price for rotator cuff repair is $5,710, or about 20% lower than SCO’s $7,159. But, once we include charges for distal clavicle excision ($1,394) and acromioplasty ($3,119), the hospital charges would add up to $10,223, making the surgery center significantly less expensive.

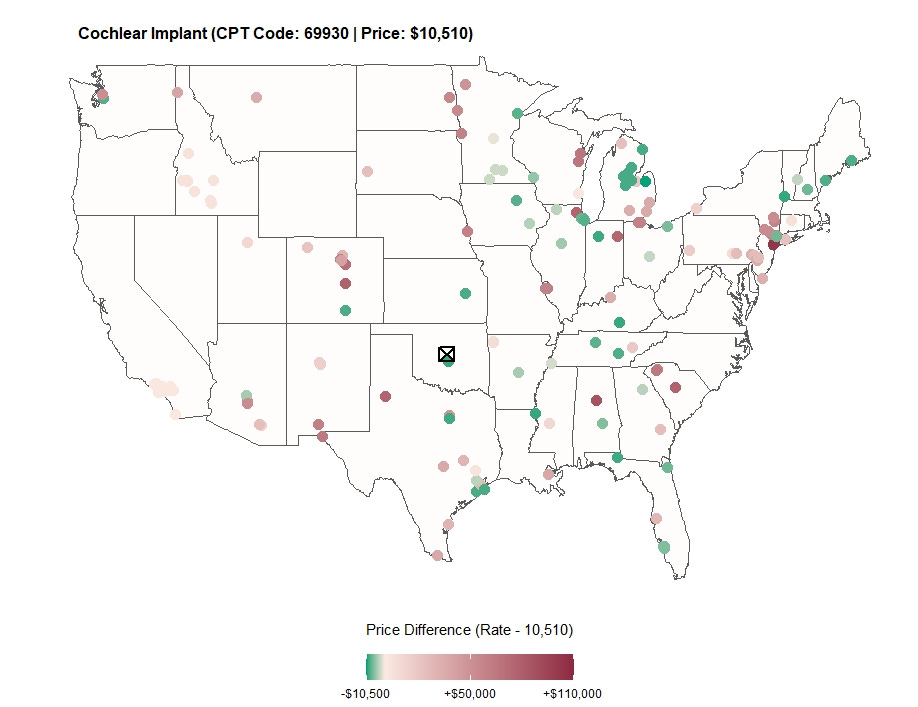

This makes a lot of sense and is not surprising if you’ve ever received a hospital bill or tuned into Kaiser Health News’s Bill Of The Month. Unfortunately, the fact that hospital prices are not all-inclusive, and therefore don't reflect all the services included in SCO's “bundle price", will always complicate these comparisons, but Dr. Smith offered one suggestion: to look at some stand-alone, single-code services. We followed Dr. Smith’s suggestion and mapped rates for cochlear implantations, a small device that aids people with severe hearing loss.

Here we found prices more in line with our expectations, with the majority of price quotes higher among hospitals. Perhaps more surprising is the range of prices offered. See for instance the cluster of hospitals in the New York City area. While it is not surprising that some of the most expensive hospitals are in NYC, it is curious how expensive they are, and how, if these results are taken at face value, a New Yorker could reduce their bill 10-fold by traveling 20 miles to White Plains Hospital over Columbia University Medical Center.

Obviously, we’ve only looked at a couple of services and wouldn’t want to make sweeping conclusions, given the limitations discussed. To examine this question in more detail would have to involve more services, statistical analysis, and a strategy to deal with the variable reporting rates that are present in the Hospital Price Data. One possibility would be to look more systematically at hospital service codes that are typically billed alone, or some variation of that.

Another thing shown in the two maps is that reporting rates vary substantially across different services. While our data and selection criteria produced close to 50 cash rates for toenail surgeries in Oklahoma alone, we only observed a couple hundred nationwide for cochlear implantations, which is one of the lessons we’re drawing from this project. Reporting rates, especially for cash prices, which represent a small fraction of hospital revenues, may not be high enough to be representative of the overall hospital industry. For comparison, we observe that five times as many hospitals have reported insurer negotiated rates for cochlear implantations than we do cash rates. Another potential solution to some of these concerns would be to look at hospital chains, where the reporting decisions are made at a corporate level.

All in all, the price transparency space is an interesting one to follow. Providers like the Surgery Center of Oklahoma are introducing price competition, and as researchers, we are now fortunate the price transparency rule and providers like Turquoise Health have made never before seen data available to study its effects. But at this point, it’s equally clear that to draw valid conclusions from this data requires a steady hand and lots of institutional knowledge about our healthcare system. So with that, we’ll get back to work!