COVID-19 Policies: Will There Be a Reckoning?

We need a resilient healthcare system to remedy delayed medical care.

I have COVID-related policy analysis fatigue, so naturally, I’ve decided to review another one. This week The Economist published an article showing healthcare systems under stress around the world. The magazine argues that the source of the stress is pent-up demand from COVID lockdown policies and delayed medical care occasioned by COVID. Several papers have shown that delayed medical care could have far-reaching consequences. In the US alone, about 9.4 million cancer screenings were missed during the pandemic. There was a 90% drop in colonoscopies; 41% of patients with chronic conditions delayed care, and so on. Overall, about a third of Americans delayed medical care due to the pandemic. Early cancer detection has direct correlation with survival chances. The reason most healthcare systems are under stress is because of the backlog in medical care. These would eventually be cleared. However, for some diseases, the delay could prove consequential.

Take colorectal cancer, for example. According to one study, by 2044 mortality from the disease could be almost 10% higher than pre-pandemic trends. For all cancers, there would be almost 100 more deaths per 100,000. In addition to delayed diagnosis or delayed treatment of chronic conditions, there are significant effects of stringent lockdown policies on mental health, particularly of adults. In the UK, for example, there was a significant increase in depression, anxiety and alcohol use, among other afflictions. (Surprisingly, a number of studies show no increase in suicide rates.)

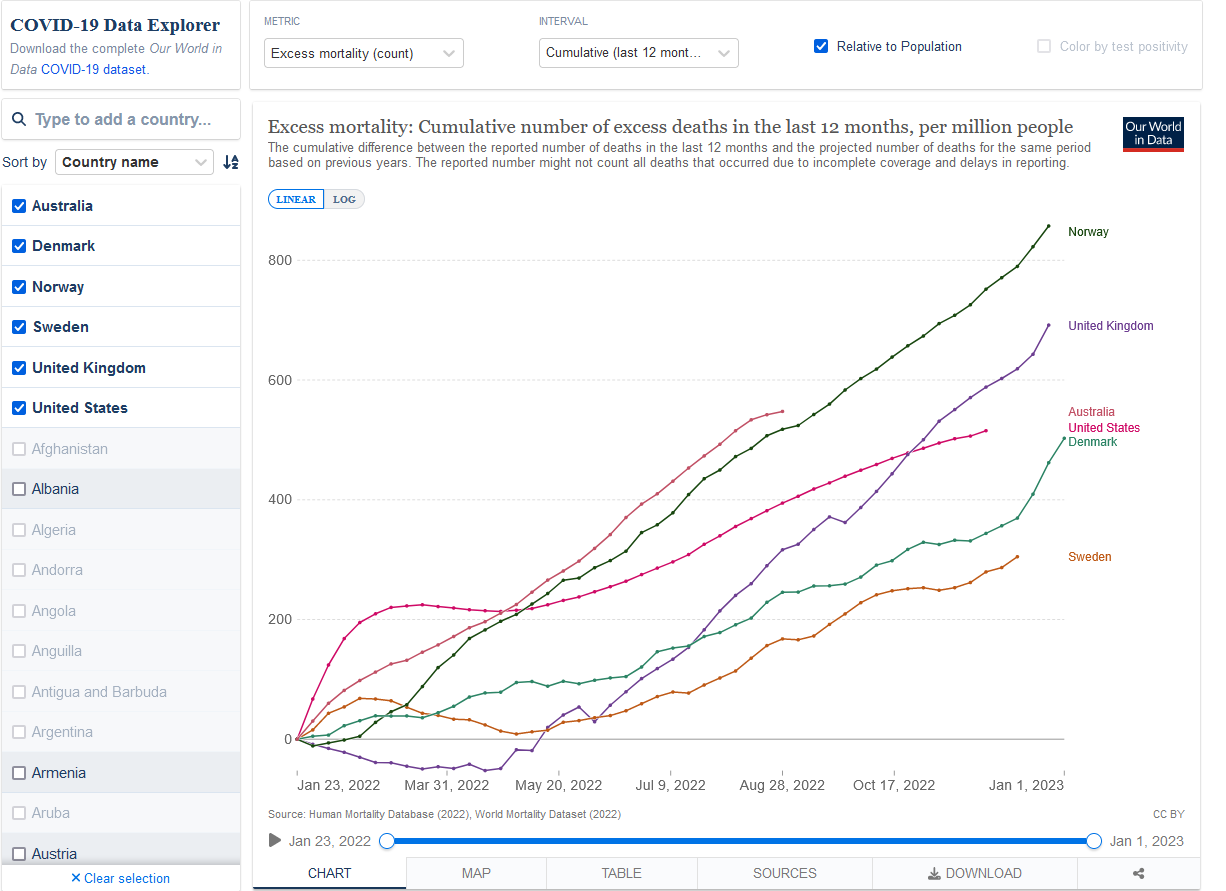

I have yet to find any studies that analyze the effects of delayed medical care in Sweden. However, we know that from other mortality analyses such as all-cause mortality, excess mortality, Sweden fared much better than countries with some of the most stringent restrictions. In a recent analysis from the UK’s Office of National Statistics, Sweden has one of the lowest excess mortality rates (almost indistinguishable from Norway and Iceland) for the period January 2020 to July 2022. Why is this still the case? This is not a rigorous study, which could rule out specious reasons. Yet, it’s somewhat surprising that over the past 12 months, Sweden has lower excess mortality than Denmark and Norway. Another puzzle is that excess mortality keeps rising even “after” the pandemic, and it is unclear when this rate would peak.

Our health systems need to be more resilient to such shocks. We will inevitably have more epidemics or pandemics. No two pandemics will ever be the same; it is possible that the Swedish approach won’t be appropriate for the next contagious disease. However, by March 2020, it was quite clear that we knew the at-risk groups. It’s surprising that the US healthcare system now seems the least stressed among the countries studied by The Economist. Without assuming any causes, it seems the US is the only one with privately provided care, though heavily regulated and expensive. According to The Economist analysis, the reason the US does better than the other countries is because of the high levels of spending (driven mostly by government expenditure, ironically – ratio of private to public per capita healthcare expenditure is higher in UK than the US). I would go further – it is exactly because we have significant private sector involvement, even in the face of all the regulatory constraints, so healthcare providers are usually independent. Several studies have documented that healthcare productivity in the US is quite high (at least compared to the UK). However, we could improve the level of productivity even further by removing several capacity barriers, many of which my colleagues have frequently addressed: regressive certificate-of-need laws, prohibiting corporate ownership, ban on physician-owned hospitals, restrictive practice scope, among others.

What great writing Sir, Thanks for this information.