Those covered under Medicaid expansion are costing much more than expected

And it's not clear why.

Last fall, The New York Times ran a widely publicized series of articles drawing attention to the fact that Medicare spending per enrollee, contrary to forecasters’ expectations, had essentially flatlined over the previous decade. “[T]he Medicare trend has been unexpectedly good for federal spending, saving taxpayers a huge amount relative to projections,” the paper reported.

While Medicare’s rosier-than-expected spending trajectory deserves to be celebrated, less attention has been paid to a similar pattern unfolding in Medicaid — only in the opposite direction.

In the early 2010s, after the ACA’s passage but before the implementation of its core provisions, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) projected that the adults becoming newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA would cost less — a lot less — to insure, on average, than other non-elderly adults already on the program. That prediction turned out to be completely wrong.

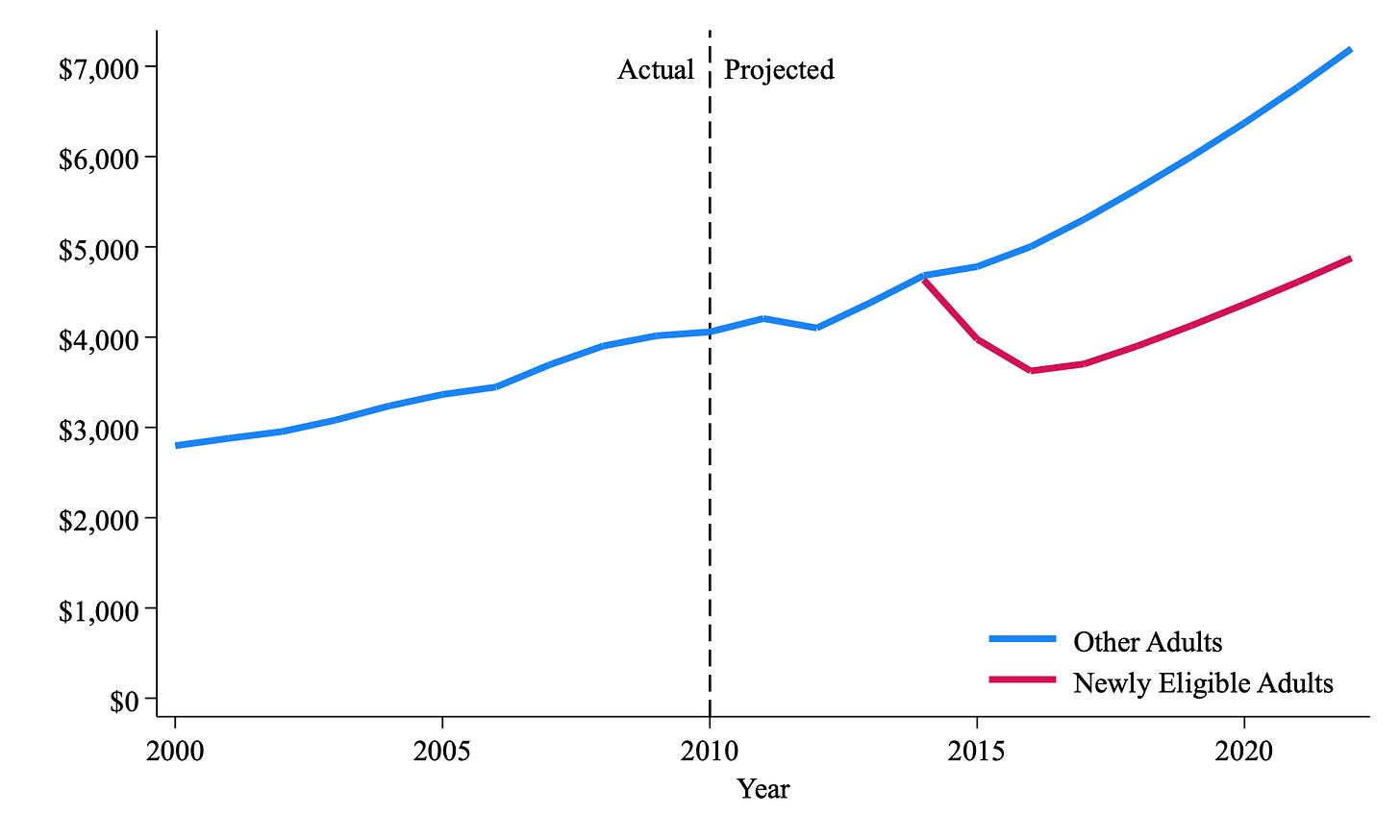

In its 2013 report on Medicaid’s financial outlook, the last analysis released before Medicaid expansion began, CMS projected per enrollee Medicaid spending for different groups of beneficiaries. That data is reproduced in Figure 1 for newly eligible adults and other non-elderly adults on Medicaid. In the first year of expansion (2014), expansion adults (the violet line) and other non-elderly adults (the blue line) were expected to cost virtually the same. But by 2016, expansion adults, on average, were projected to only cost between two-thirds and three-quarters of what other non-elderly adults cost. Moreover, the gap was expected to gradually increase over time, with per enrollee spending on other non-elderly adults rising slightly faster than per enrollee spending on newly eligible enrollees. In 2022, the last year in the projection window, CMS predicted that expansion adults would cost $4,875 per enrollee, while other non-elderly adults were expected to cost $7,195 per enrollee — nearly 50 percent more.

CMS thought that newly eligible enrollees would be relatively inexpensive to insure for three reasons: 1) they would be in fairly good health — otherwise they would qualify for Medicaid under pre-ACA rules (e.g., by receiving Supplemental Security Income); 2) large numbers of people with low health spending, especially young adults, would join Medicaid under the ACA, dragging down the average spending per enrollee; and 3) per enrollee spending on newly eligible adults would moderate after an initial surge in costs in the first year or two as individuals who had not previously had their medical needs adequately met began accessing services (i.e., “pent-up” demand).

Though its assumptions appear reasonable, CMS’ actuaries blundered, recent data shows. Table 1 contrasts the predicted levels of spending for each eligibility group with the actual levels of spending in 2019. (More recent data is available, but may be distorted by the COVID pandemic. CMS can hardly be blamed for failing to foresee a once-in-a-century health crisis.)

Not only did actual spending on newly eligible adults far exceed projections, but actual spending on other non-elderly adults came in well below expectations. What’s going here?

I don’t think anyone has a fully satisfactory answer. But with hundreds of billions of dollars at stake, more scholars should be tackling this question.

One potential explanation is the opioid epidemic. The severity of the opioid crisis over the last decade could not have been accurately predicted in 2013. Medicaid expansion has increased treatment for opioid addiction at a substantial fiscal cost, and it seems plausible that expansion adults may be more likely to use drugs and avail themselves of addiction treatment than other non-elderly adults.

My Mercatus colleague Charles Blahous has argued that institutional incentives may have played a role as well. The enhanced federal funding for expansion adults may have made states less vigilant about containing costs for this population.

Some of my ongoing research touches on this theme. The data suggests that states have reclassified some Medicaid enrollees from the “non-expansion” group (i.e., individuals who are eligible under pre-ACA rules) to the newly eligible group. Since per enrollee costs in the non-expansion group are much higher than in the newly eligible group (driven mostly by high spending on the aged and those with disabilities), these reclassifications serve to artificially inflate per enrollee spending in the newly eligible group. Audits carried out by the federal government in California, New York, and Colorado (all of which expanded Medicaid) suggest that about 10-25% of enrollees classified as newly eligible under the ACA are, in fact, either ineligible for coverage or misclassified.

Forecasting is, of course, a highly imprecise exercise. I don’t fault CMS for making mistakes. But the evidence from Medicare and Medicaid over the last decade should make us skeptical of anyone’s ability to accurately foresee all the consequences — intended and unintended — of policy reforms.