Conservative Health Policy: A Quick Look at The Wins We Celebrate

In his recent blog post, Conservative Health Policy, my colleague Kofi Ampaabeng captured a sentiment I think many market-oriented scholars like myself have felt for a long time: “Even before the ‘Great Society’ policy wins of the left, US health policy had been trending leftward and continues to do so [today].”

This got me thinking, what are the most significant market-oriented health policy achievements of the last 30-50 years? It’s a fun question to ponder, and the answer depends no doubt on your perspective, how you define a policy achievement, and so on. Instead of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, I’ve taken a stab at it by quickly going through some milestones.

The first three relate to insurance markets and are all popular with others, though less so with me. If you have your own insights, I welcome your comments below, or a message in all caps, explaining what I’m missing.

The Popular

The first contender would surely be Health Savings Accounts (HSA’s), signed into law in 2003 by the younger President Bush, and now capturing more than 100 billion dollars across 35 million accounts, allowing Americans to make tax-advantaged contributions earmarked for medical expenditures when enrolled in a high-deductible health plan (HDHP). By requiring HDHP enrollment, HSA’s bring prices faced by consumers closer to their true cost and encourage competition by incentivizing consumers shop for better prices and quality, both key market principles.

In theory, this sounds pretty good, and this paper shows consumer directed plans do reduce spending on outpatient care and prescription drugs, but I have to say I’m skeptical that HSAs will do much to improve our healthcare system, primarily because what seems to me the key benefit for our healthcare system — prices closer to cost — has been happening in many other plans as well, and because healthcare services, especially some of the expensive ones where the bulk of the spending occurs, just don’t seem all that “shoppable.”

Another policy that gets mentioned is the growth of capitated insurance plans through Medicare Advantage (MA). These plans are a step away from fee-for-service, instead paying a fixed rate per enrollee to a sponsor, who then competes by offering a bundle of networks and services to consumers. Choice is great, and MA plans are popular among consumers, but my main issue with Part C is that it does little to reduce spending through cost-sharing or other means — in fact, it seems plausible a lot of its popularity is exactly because it doesn’t do this.

Relatedly, some people bring up Medicare Part D, a voluntary prescription-drug benefit for seniors, as a win. Why subsidizing prescription drugs for seniors, many of whom were perfectly capable of planning for themselves and purchasing insurance on their own, was a good idea was always a bit of a puzzle to me. That puzzle has only grown now that the key aspect to control cost in Part D’s original design, the infamous “donut hole” where participants were responsible for much or even the entire cost of drugs over a certain range, was closed in 2020.

The Forgotten Hero

The innovation of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry is one of the greatest success stories in U.S. healthcare: saving lives for as little as $2-16,000 per life-year, far cheaper than many other interventions. Had this post not already been contrarian I might have proceeded to make a case for this, in and of itself, but instead I’ll dial it back to say there are good arguments to be made for the 1984 passage of the Hatch-Waxman Act.

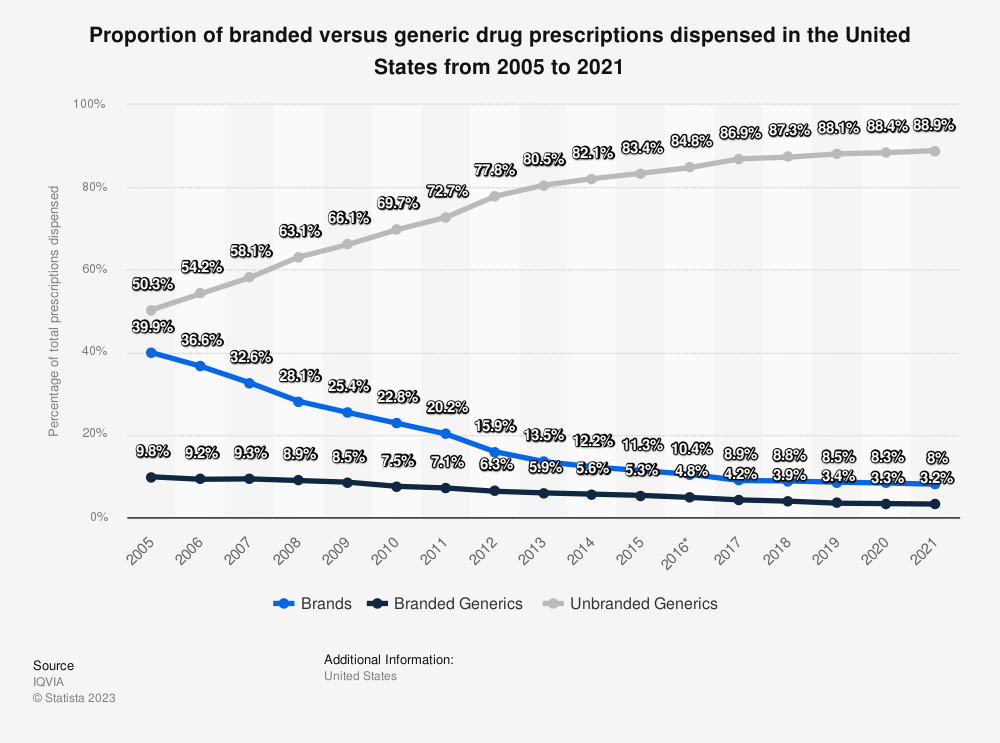

Hatch-Waxman managed to introduce, albeit imperfectly, competition from generic drug manufacturers bringing sharp reductions in prices, while preserving the incentives for innovation in search of the next block-buster drug. I say imperfectly because, as my colleagues Justin Leventhal and Kofi Ampaabeng pointed out, drug manufacturers have found ways to take advantage of loopholes including evergreening, the practice of preserving their patent-protected monopolies by making tiny tweaks to a drug with little or no benefit to patients — think placing pills inside of capsules, and similar strategies.

But while evergreening and the Martin’s Shkrelis of the world give U.S. pharma a bad rep, a picture says a thousand words, and it’s clear Hatch-Waxman has been a great success. Generics have gone from 13% of the market in 1983, to almost 90% today, bringing products previously unimaginable to consumers at prices that rapidly approach the cost of production, once generics enter the market.

In the interest of brevity, I’ll conclude by noting that there are cases to be made, cases I will entertain in a future post, for Operation Warp Speed, the current unwinding of the public health emergency, and maybe even aspects of the Affordable Care Act as major policy wins for which there might be cause to celebrate.

What else should we celebrate: the Price Transparency orders under Trump? The Supreme Court overturning Roe? Welfare Reform of the 90’s? Do let me know below.

To go further, please check out the following pieces:

(Kofi Ampaabeng)

Drug Shortages and Drug Prices

(Kofi Ampaabeng)

Biden Budget: Summary and Assessment of Medicaid Items

(Peter Nelson and Elise Amez-Droz)

Fine piece, as usual, Markus. A couple of years ago, Chuck Blahous and I wrote a piece called "Leftward, Ho!" (https://www.discoursemagazine.com/politics/2020/10/19/leftward-ho/). In it, we wrote, "In fact, in recent years the drift of US policy has been vigorously leftward. Even conservatives have moved somewhat to the left, while liberals have moved sharply in that direction. Indeed, there are few if any policy areas where either end of the spectrum (either party, if you wish) has moved rightward.

The trope (conservatives moving sharply right, liberals moving slightly left) appears to be an illusion borne of a moving reference point—in this case, the leftward-shifting political center. It resembles a passenger on a 350-mile-per-hour westward-bound airplane saying, “Wow! New York City is moving eastward at 350 miles per hour!” A more precise analogy would be that it’s like a passenger on the same plane observing a 50-mile-per-hour westward-bound train below and convincing himself that the train is moving eastward, in reverse, at 300 miles per hour. When too many authors write about political polarization, they in effect describe the behavior or distribution of passengers inside the moving plane or train but neglect the fact that both vehicles are moving west (left)."